Physician’s Resources

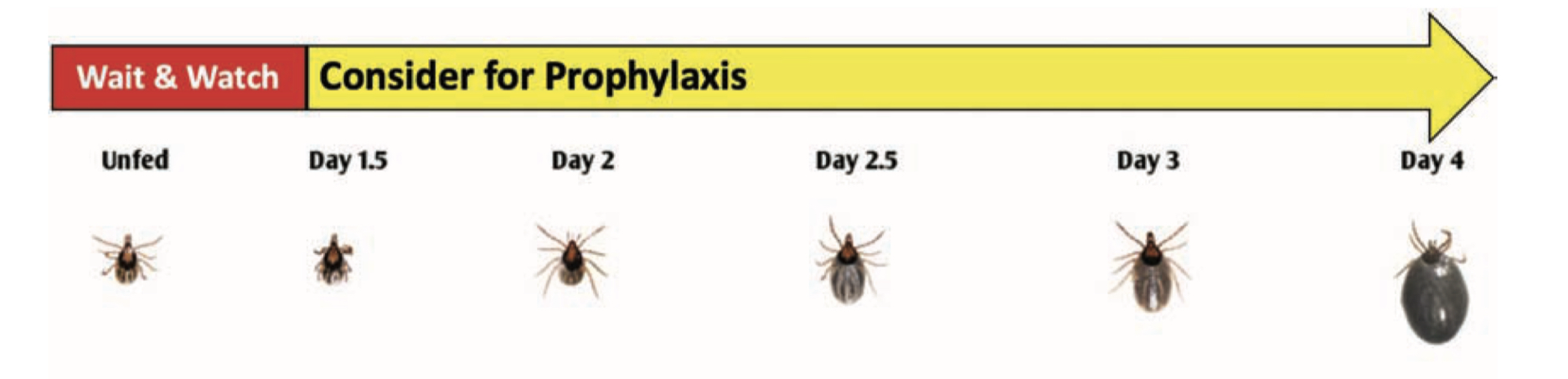

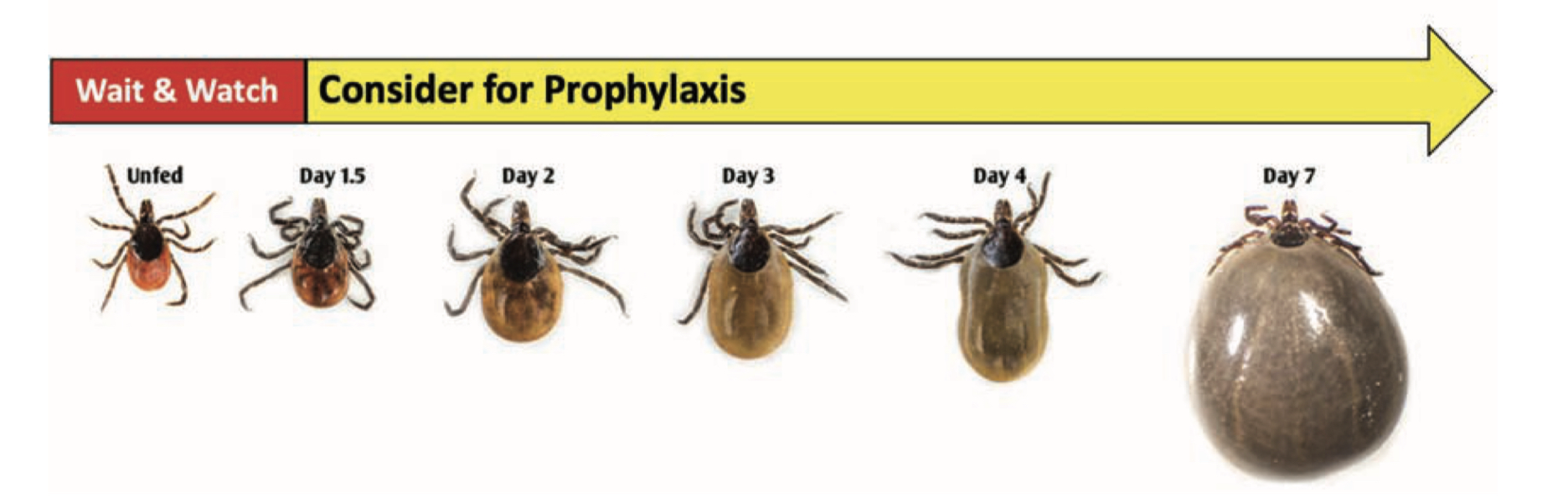

Considerations for Chemoprophylaxis Based on Tick Engorgement

Chemoprophylaxis may be considered in regions endemic for Lyme disease if a tick has fed for more than 36 hours.

Nymphal Stage

Adult Female

Early Localized Lyme Disease

- Erythema migrans (EM) rash

- Occurs in approximately 60 to 80 percent of infected persons

- Begins at the site of a tick bite after a delay of 3 to 30 days (typically 7-14 days)

- A tick bite at that skin site, however, is only recalled/noticed by ~25% of patients with a single EM skin lesion in the US

- Is typically a red and annular shaped skin rash that is at least 2 inches in diameter

- Expands gradually over several days reaching up to 12 inches or more (30 cm) in diameter

- May feel warm to the touch but is rarely very itchy or very painful

- Sometimes partially clears as it enlarges, resulting in a target or “bull’s-eye” appearance

- May appear on any area of the body

The “Bulls-Eye” Rash or Erythema Migrans (EM) is one of the classic symptoms of early localized Lyme disease. EM is not always a distinctive bulls-eye – sometimes it is more uniform in appearance, or faint in color – particularly in folks with darker skin. It’s also important to note that not all EM like rashes are a result of Lyme disease, so the circumstances surrounding a rash are always important for diagnosis. Swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) may occur near the site of the EM rash.

- Fever, chills, headache, fatigue, and/or muscle and joint aches may occur in early Lyme disease in patients with EM, but can also occur from B. burgdorferi infection in the absence of EM.

Lyme Arthritis

Early Neurologic Lyme Disease

Cranial nerve symptoms: facial nerve weakness (facial palsy/drooping), which can occur asymmetrically or symmetrically.

Peripheral nerve involvement: radiculoneuropathy which can cause numbness, tingling, “shooting” pain, or weakness in the arms or legs.

Central nervous system symptoms: Lyme meningitis (inflammation of the meninges) with fever, headache, sensitivity to light, and stiff neck.

Lyme Carditis

Lyme Carditis (occurs days to months after tick bite):

Lyme carditis can occur when B. burgdorferi spreads to the heart tissue, which can interfere with normal heart function. Lyme carditis, however, occurs in fewer than 1% of Lyme disease cases.

Lyme carditis can cause light-headedness, fainting, shortness of breath, heart palpitations, or chest pain.

Carditis can interfere with the normal beating of the heart, leading to “heart block,” which can vary in degree. While Lyme carditis can potentially be fatal, that is extremely rare. There have been 11 cases of fatal Lyme carditis reported globally over a period of 34 years (1985-2019).

How do we diagnose Lyme disease?

The diagnosis of early Lyme disease presenting with EM (erythema migrans) is clinical. The characteristic skin lesion present at the site of an Ixodes scapularis tick bite in individuals living in Lyme endemic regions is diagnostic.

Laboratory diagnosis is recommended in patients suspected of having Lyme disease from Lyme endemic areas presenting with atypical skin lesions, disseminated disease such as multiple skin lesions, neurological (meningitis, facial nerve palsy) or cardiac (myocarditis, atrio-ventricular block) symptoms, as well as those with arthritis that develops few weeks or months after the infection.

Since Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium (Borrelia burgdorferi) that is difficult to culture and is present in low numbers in clinical samples during early stages of infection, the main modality of laboratory confirmation is the detection of antibodies to the microorganism (Serology).

The current guidelines for antibody testing include the use of a 2-step testing. The first step uses an antibody assay such as an Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) that has high sensitivity to detect IgG and IgM antibodies to B. burgdorferi (Bb); if this first step test is positive, it is followed by a second step EIA that will confirm the first step. The second step can use IgG and IgM western blots (WB) or immunoblots (IB) (Standard two-tier testing, STTT), or another EIA that uses different antigens than the first step (Modified two-tier testing, MTTT). The STTT uses IB interpretation criteria for IgG and IgM that had been previously evaluated and published. The IgM IB criteria uses 3 blot bands (41, 39 and 23-kDa, OspC) and the IgG IB criteria uses 10 bands (93, 66, 58, 45, 41, 39 30 28 and 23 and 18-kDa). In order to fulfill the IgM criteria, 2 of those 3 bands need to be detected and 5 of those 10 bands for IgG IB. Since these guidelines were adopted at the Second conference on Lyme diagnostics in Dearborn MI, and the Centers for Disease Control was one of the sponsors, it became known as the “CDC criteria”. Besides the bands to be scored, the guidelines established that the IgM IB criteria is only to be used during the first 4 weeks of early disease, but the IgG at any stage of the disease. The advantage of the MTTT is that IB, that suffer from interpretation limitations, are not used in addition to eliminating the 4-week IgM blot restriction. The two-step testing has limited sensitivity during early disease with EM (25 – 50% in acute sample to about 70% in convalescent phase sample) but increases to over 70 % to 100% in samples from patients with disseminated or extracutaneous manifestations of Lyme disease.

What are the limitations of current diagnostics?

The limitations are predominantly due to the complexity of B. burgdorferi (Bb) and those of serology.

The ideal laboratory method to support the diagnosis of an infectious disease is the direct detection of the organism causing disease, that in Lyme disease is difficult since Bb is not usually detected in clinical samples. Detecting antibodies is an indirect method that suffers limitations since it relies on the immune response of an infected individual to the antigens expressed by the infecting microorganism.

Regarding the complexity of Bb, this bacterium possesses most of the genes encoding its important antigens in plasmids, rather than in the chromosome. This allows Bb the plasticity to express antigens according to the environment that encounters. These antigens might differ when Bb is in a tick midgut or in the tissues of an infected mammal. As Bb is transmitted by a tick to a human, the antigens expressed by the microorganism stimulate the immune system leading to the development of antibodies that can vary depending on the patient’s immune response, the microorganism pathogenic characteristics, the antigens expressed and the duration of disease.

But the complexity of Bb goes beyond geographic boundaries. Bb causing infections in different geographic locations in the northern hemisphere are heterogeneous leading to different clinical manifestations. There are over 20 genospecies within Bb, being B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Bbss), the most frequent causing infection in North America. B. afzellii and B. garinii along with Bbss cause Lyme disease in Europe. While all genospecies cause LD with EM, they differ in the later manifestations that they cause.

In addition to the antigenic complexities and geographic variations, antibodies to microorganisms appear within weeks, therefore they might not be detectable during early stages of the infection. That is the reason why serology works better when acute and convalescent phase samples are tested. If diagnostic antibodies are not present during the acute phase, they might be during the convalescence. Serology is not the recommended test when patient presents with a classical EM but might be useful in later disease stages as indicated above.

Other limitations of serology for Lyme disease include the persistence of detectable antibodies even after the disease has successfully been treated; therefore, serology is not recommended to follow the effect of treatment. In addition, the presence of antibodies as detected by these tests does not confer protection and these antibodies do not correlate with disease activity.

What are the current updates on new Lyme diagnostics?

Most current advances in Lyme diagnostics have dealt with searching and identifying antigens that could be used in more sophisticated assays, such as multiplex antibody assays using flow cytometry or on a chip. Other methods such as metabolomics or proteomics looking at signature biomarkers are being evaluated but as of now, they are not ready for diagnostic use.

What are ways Lyme cannot be diagnosed? (types of tests to avoid, can we list brands?)

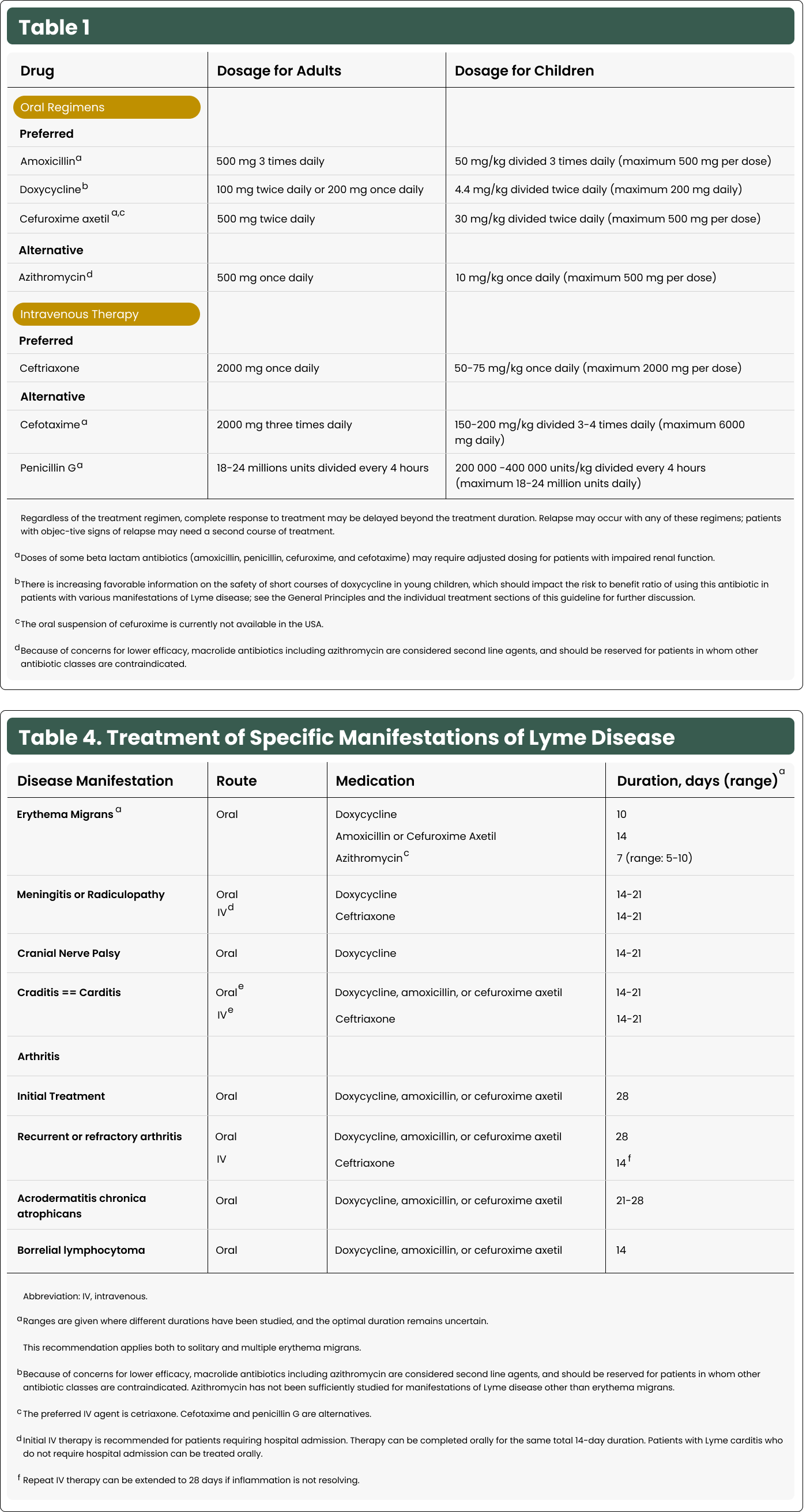

All treatments approved and supported by available evidence are the use of antibiotics to clear this bacterial infection. Lyme disease, regardless of whether it remains localized at the site of the tick bite or is one of the 10-20% of infections that has disseminated to another body site, is caused by a bacterial infection. As such, antibiotics, which are chemicals that kill bacteria, are typically successfully used. Treatments are standardized and reviewed periodically by reputable organizations such as the CDC, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and others. There are 3 main oral antibiotics that are prescribed for Lyme infections. Dosage depends on age and duration on the clinical presentation. If you have contraindications to these 3: doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime, there are second-line antibiotics that can be used.